How SCADA Systems get Compromised

High-Level Walkthrough of Industrial Exposure

ARTICLES

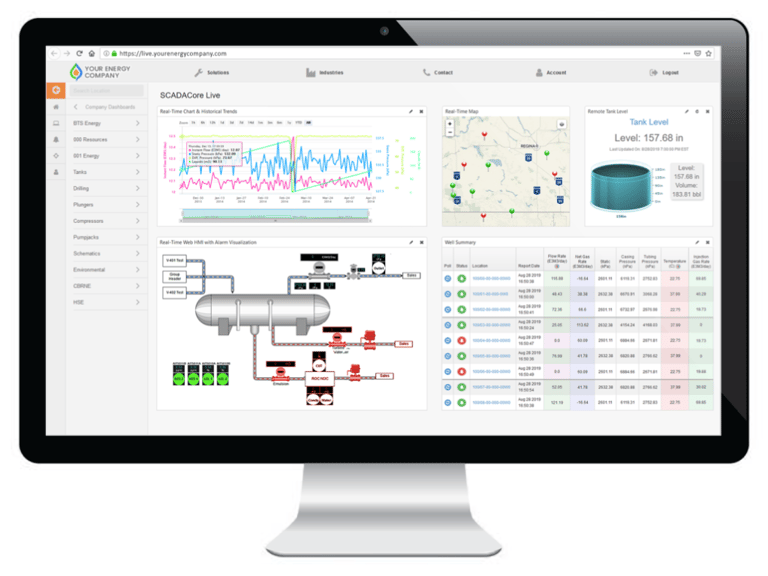

SCADA systems control things that matter in the real world like electricity, water treatment, manufacturing lines, oil and gas pipelines. Unlike traditional IT systems, SCADA environments were designed decades ago with reliability in mind, not security. Many of these systems were never meant to be connected to the internet, yet today they often are.

For decades, these systems operated in isolation. Today, remote access, cloud monitoring, and IT–OT convergence have dissolved those boundaries. The result is an environment where exposure often goes unnoticed, not because attackers are sophisticated, but because defenders assume isolation still exists.

What is SCADA?

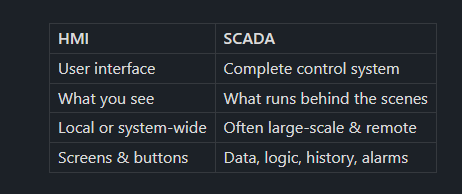

SCADA is the entire system used to collect data and control processes, often over large areas.

In simple terms:

SCADA = the whole monitoring & control system

What SCADA does:

Collects data from sensors and machines

Sends commands to equipment

Stores historical data

Manages alarms and events

Enables remote monitoring (sometimes over cities or countries)

What is HMI?

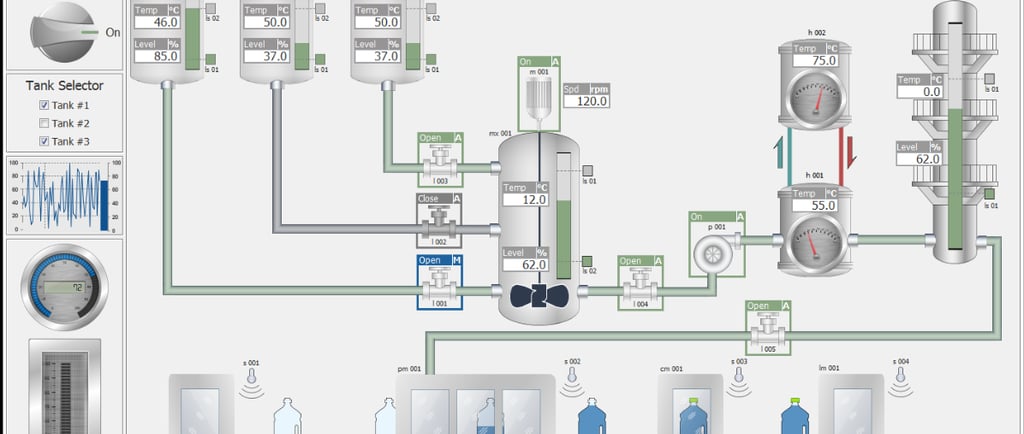

HMI (Human–Machine Interface) and SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) are closely related systems used to monitor and control industrial processes like factories, power plants, water systems, and transportation.

An HMI is the visual interface that humans use to interact with machines or processes.

In simple terms:

HMI = the screen operators look at and touch

Key Difference (Easy to Remember)

UNDERSTANDING THE SCADA MINDSET

Before any terminal is opened, it’s important to understand how SCADA environments differ from IT networks.

SCADA systems:

Run continuously with little tolerance for downtime

Use legacy protocols like Modbus and DNP3

Often lack authentication or encryption

Are managed by engineers, not security teams

Prioritize availability over confidentiality

Attackers know this. More importantly, so do incident responders. That’s why most real-world SCADA incidents begin with exposure and observation.

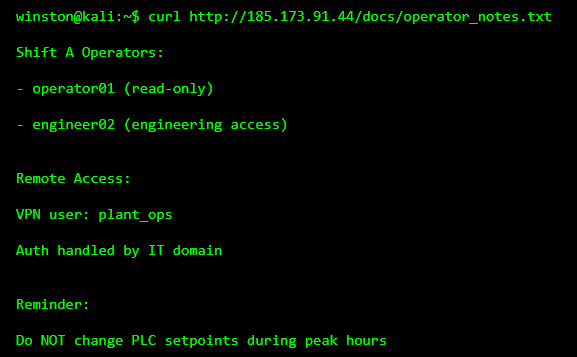

STEP 1: IDENTIFYING AN EXPOSED INDUSTRIAL SYSTEM

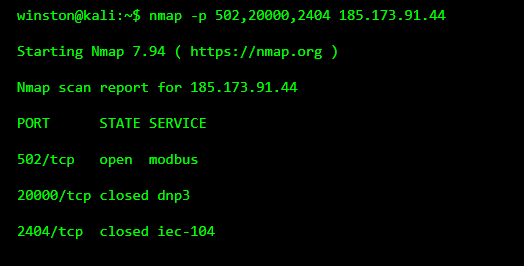

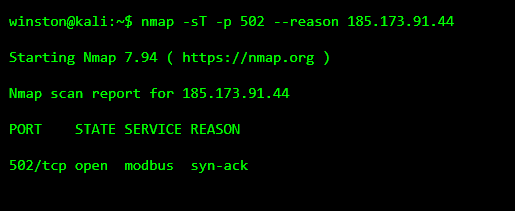

In many investigations, the first sign of trouble is discovering an industrial protocol reachable from an untrusted network. Analysts often check for well-known ICS ports to understand what kind of environment they’re dealing with.

At this point, nothing has been touched. Yet the presence of Modbus alone already signals risk. Modbus has no authentication, no encryption, and assumes trusted networks. If it’s reachable from outside a protected zone, the environment is already fragile.

WHY THIS MATTERS IMMEDIATELY

Many people assume an attack hasn’t happened until something breaks. In SCADA environments, that assumption is dangerous. Exposure is the incident.

This single response tells an attacker that:

A PLC or RTU is reachable

Network segmentation is weak

Legacy protocols are exposed

STEP 2: CONFIRMING A LIVE INDUSTRIAL DEVICE

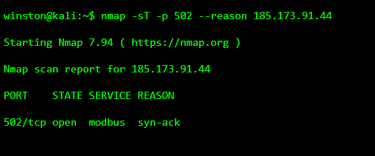

Before going further, hackers confirm that the service is genuinely responding and not a misidentified port. Even minimal confirmation helps determine whether the device is live.

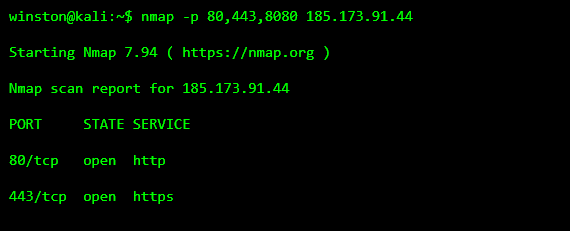

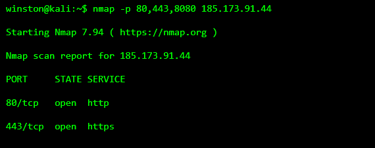

STEP 3: LOOKING FOR A HUMAN INTERFACE

SCADA environments rarely expose PLCs alone. They often expose HMIs which are web-based dashboards used by operators and engineers to monitor processes remotely.

Attackers look for these because:

They’re often read-only

They reveal process state

They reuse IT infrastructure

They don’t immediately affect operations

This is where SCADA compromises often transition from OT into IT territory.

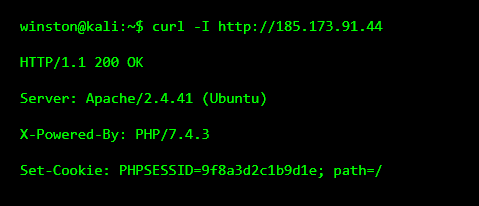

STEP 4: FINGERPRINTING THE HMI ENVIRONMENT

Even without logging in, HMIs often leak information through headers, cookies, and server responses. This tells attackers what kind of system they’re dealing with.

This confirms:

A Linux-based HMI

Session-based authentication

An IT-managed web stack

At this point, attackers rarely touch the PLCs. Instead, they start looking for supporting artifacts.

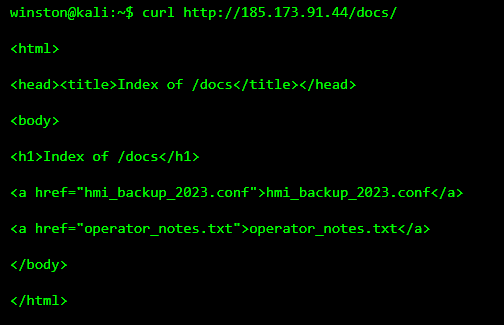

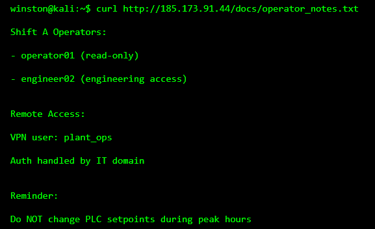

STEP 5: DISCOVERING EXPOSED ENGINEERING FILES

In many real incidents, escalation happens not through exploits, but through forgotten files. Engineers leave behind documentation, backups, and notes during maintenance.

This is often the moment hackers love.

STEP 6: FINDING SOMETHING IMPORTANT

Reviewing these files frequently reveals operational context that was never meant to leave the control room.

We did not crack any passwords neither did we touch any PLC, yet we know:

Valid account names

Role separation

That VPN authentication is handled by IT

How operations are structured

This is how SCADA compromises escalate.

WHY THIS IS ALREADY A FULL COMPROMISE

At this stage:

Process visibility exists

Engineering roles are mapped

IT–OT trust boundaries are exposed

In real-world incidents, attackers often stop here and wait. The most dangerous SCADA attacks are not rushed.

REAL-WORLD CONTEXT

Major industrial incidents, including those involving Stuxnet, did not begin with destructive commands. They began with access, understanding, and patience.

That pattern hasn’t changed.

TILL WE MEET AGAIN.